When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.Heres how it works.

But does the reality stand up?

To find out, we talk to four solo developers to discover their experiences.

How lonely is it to make games without a team in support?

What kinds of compromises artistic and financial are required?

And is all the risk worth it to be master of your own destiny?

Tomas Sala

This feature originally appeared in Edge Magazine.

Tomas Sala clearly has no regrets about leaving behind the corporate cage he helped to build.

“I hate fucking Scrum and Trello, all this fucking Jira,” he spits.

“It drives me up the wall.”

“I am incredibly chaotic,” he admits.

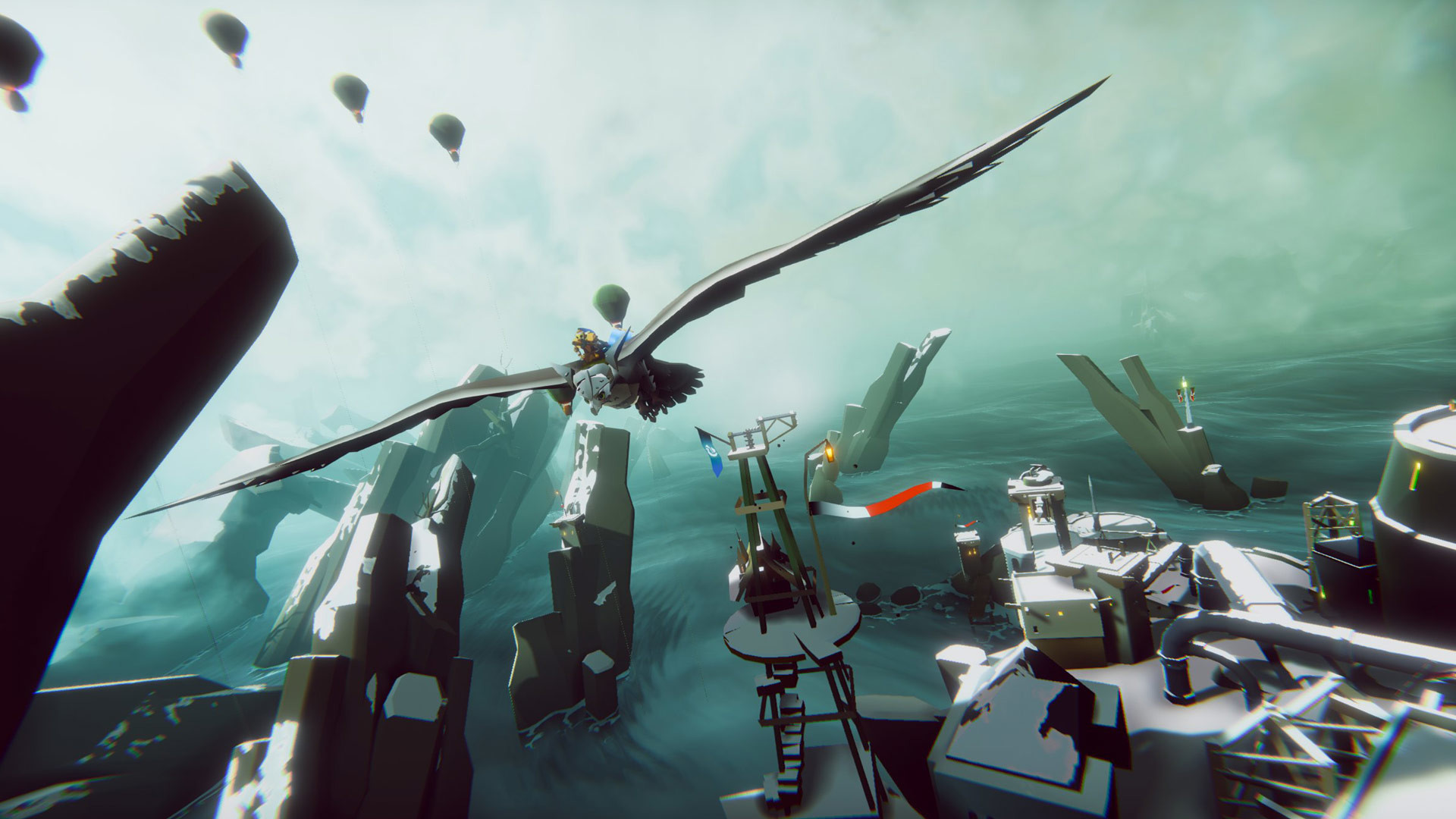

Sala started making mods to decompress, eventually releasing the Skyrim-based Moonpath To Elsweyr in 2017.

The Falconeer, a breezy aerial combat adventure inspired by Crimson Skies, was the result.

It’s tempting to see it as a reflection of his flight from the corporate world.

It’s certainly a freedom in which he has revelled.

“I love feature creep,” he says.

“It’s my entire design philosophy.”

Getting to this point of safety, though, has been a rocky road.

The hard-won release of The Falconeer in 2020 was undermined by his relentless perfectionism and feelings of impostor syndrome.

“Every negative review hits like ten, and every positive like one,” he explains.

Sala admits he is something of a workaholic.

“My only response when things get stressful is to work harder,” he laments.

Nevertheless, the fear persists.

Your internal artistic critic that says ‘this is crap’ is always rearing its head."

“Back then they were putting out one or two mobile games a week,” she says.

“It was really crazy.

“I just didnt like mobile games at this point.

I was feeling a bit icky about them.”

“I didnt really want to do that,” she says.

“Money’s not a huge driver for me, but being creative and learning is.”

“My 3D art was OK, but it wasnt great.

My 2D art was all right, but not good enough.”

It was a predicament that left her feeling stuck.

But going solo had another cost.

“It was really sad to leave that and just be on my own.”

Moving to Germany after her partner secured a job at Nintendo only exacerbated that loneliness.

Which I do love, but I’m always exhausted by the end of it.

It’s not a nice [day-to-day] balance, like you get in an office.”

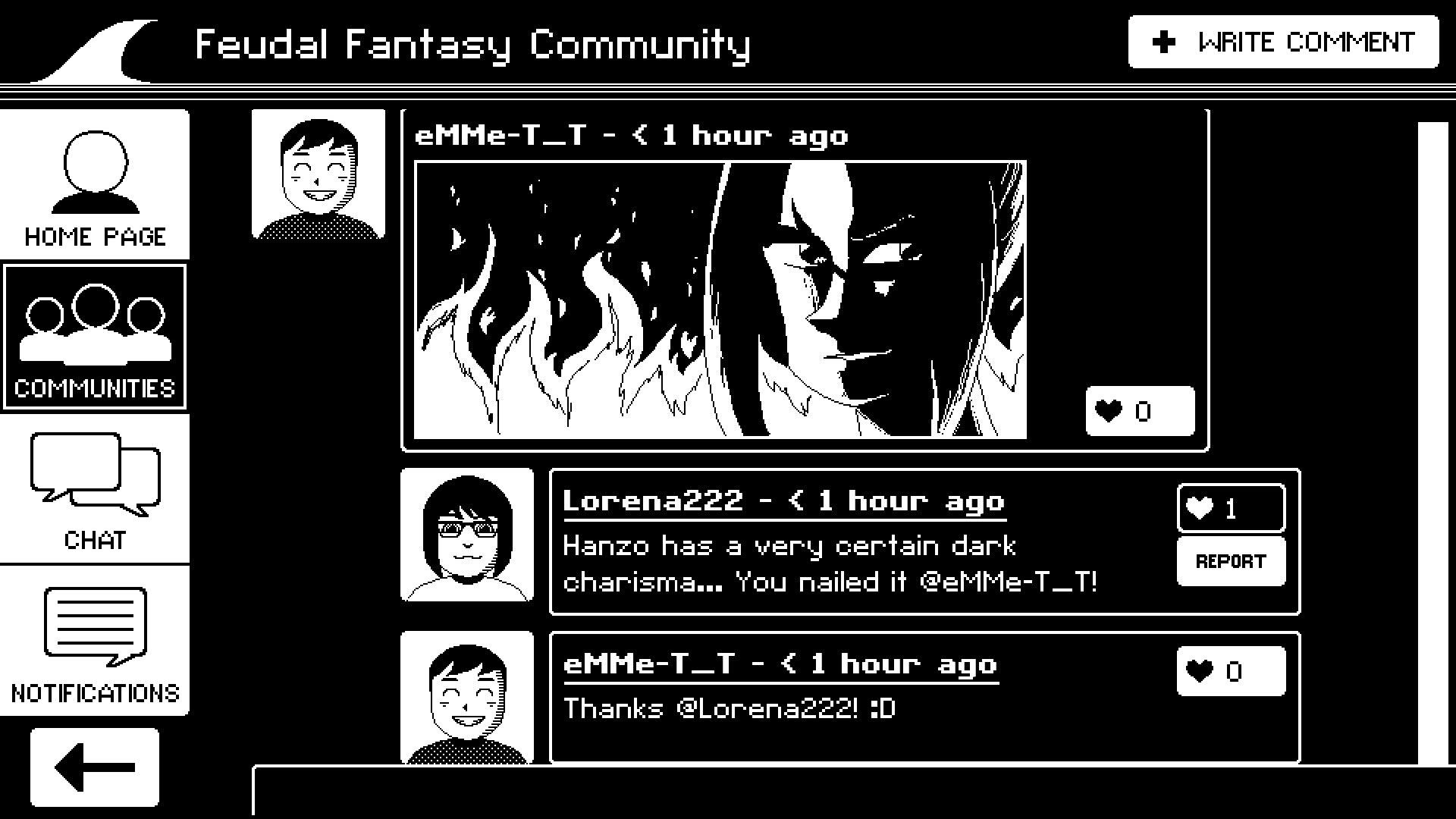

Blundell’s first big project as a solo dev, Love IRL, was never finished.

“These routes are all pretty much as long as that beginning,” she says.

She realised that coding those four branches, around 12 hours in total, could take another four years.

“And it was like, ‘Oh my god, I can’t do that’.”

She tried altering the scope of the project, but it felt like too much of a compromise.

“It was just done in like a month, and then I put it out.

No fanfare, didn’t contact anyone, just put it on Itch.io and then I went on holiday.

And while I was away it started getting covered by really big YouTubers.”

So Blundell set about polishing and updating the game, then released a paid version on Steam for 2.99.

At least, as long as she lives thriftily.

Even then, it was for work."

Blundells next project followed a similar trajectory to Love IRL.

She reckoned that would be a quick turnaround, taking no more than a year.

It ended up taking three.

“And thats quite scary.

Hurry up!'”

Along the way, a lot of elements were cut one positive, for Blundell, of working alone.

“I’m only hurting myself when I do that.

Not every solo developer comes from inside the game industry.

“For most of my life, I just wanted to teach kindergarten,” she says.

It was during her education degree, during a class on teaching math, that Karrh had her awakening.

“And then I learned how to code, and loved code even more.

So that’s when I switched my major to computer science.”

This one wouldn’t.

Faced with a desperately unfulfilling day job, she turned to making video games as a creative outlet.

And then I fell back in love with them in my 20s.”

She put out her first project, Whimsy, in 2019.

At least, not the traditional kind.

Chicago-based Level Ex is a supplier of what Karrh calls “very gross medical simulations” for doctors.

But she acknowledges that her experiences influenced her later games.

This was made possible in part by WINGS Interactive, which provides funding for women and marginalised gender developers.

‘I thought all your money comes when you release the game."

Still, it took a while for her to adapt to going solo.

Because nothing happened while you were gone."

There’s also, again, the fear.

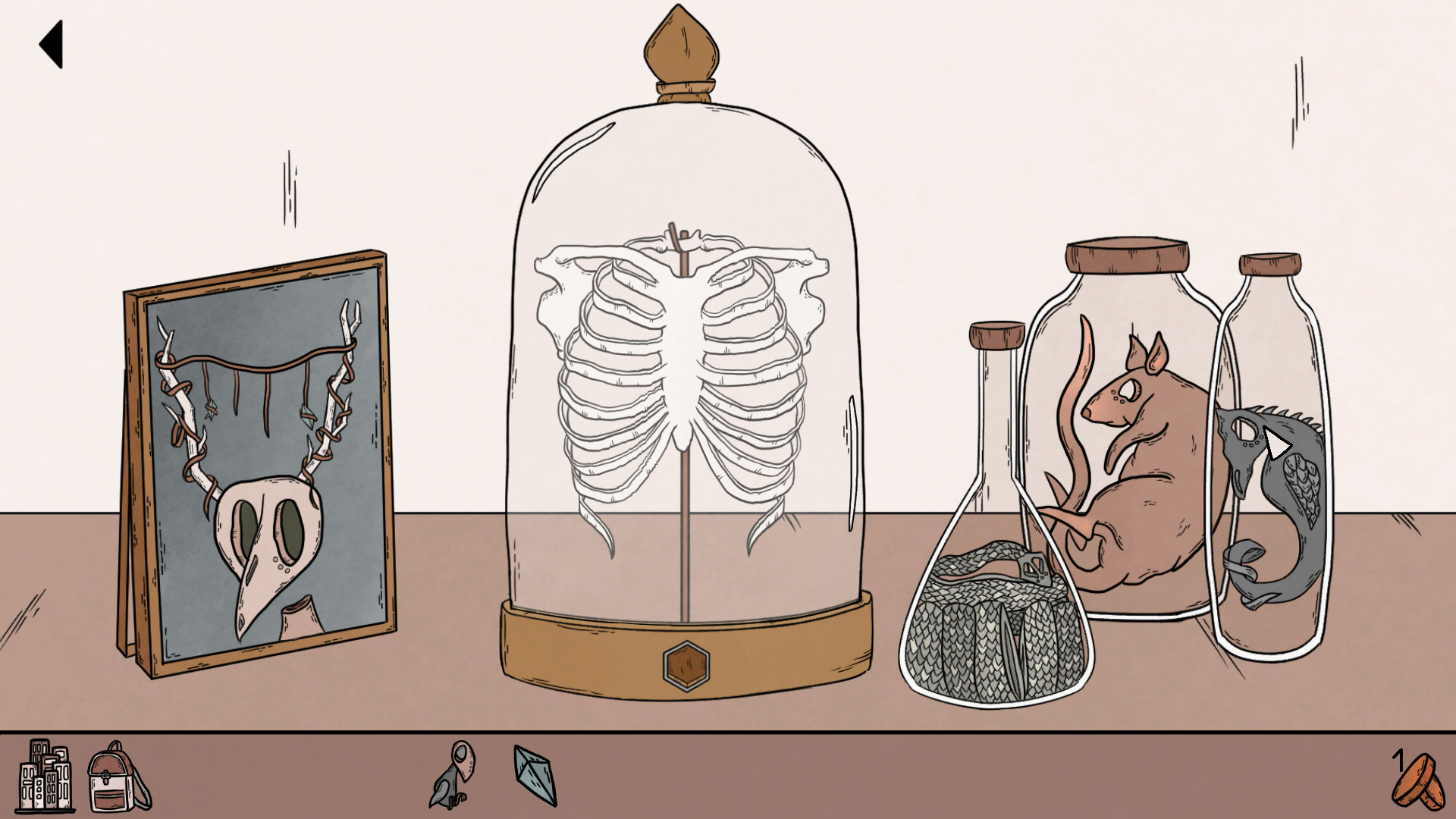

Karrh says that sales of Birth were initially disappointing, with fewer than expected Steam wishlist conversions.

It was only after several TikTokkers made videos about the game that things picked up.

“I feel the fear a little less now,” she says.

I also know that you’re able to make something while youre working full-time.

He reasoned that if the game did well, he’d be able to continue as a developer.

“And if it didn’t, I’d have to get a real job,” he says.

“And then I released it, and it did very, very, very badly.

It sold 15 copies on day one.”

And then silence from PewDiePie, silence from the world."

He sent out a few speculative applications to small game studios, but his heart wasn’t in it.

“Secretly I was fully focused on just making another game,” he says.

I should make what I want, because I’m capable of making something great.

But times were desperate.

So what kept him going?

He partly attributes his resistance to getting a ‘real job’ to his social awkwardness and anxiety.

“But also an inflated sense of my own self-worth,” he says.

“I felt like I should be making my own thing, not making someone else’s thing.”

Like Sala, he enjoys being able to do as he wants.

I think that ultimately what makes an artist an artist is that theyre an arrogant prick."

Yet Richardson is also incredibly self-deprecating about his work.

So how does this square with his supposedly inflated sense of self-worth?

“So I think I’m also making shit.

Though Four Last Things wasn’t a big success, it sold enough for Richardson to justify keeping going.

He was still picking up shifts at the screen-printing studio, but occasionally started saying no to work.

The game has continued to sell steadily.

“For the two years after release, I was rich,” he laughs.

“But I know I’m not.

If that was my actual salary, Id be rich.

But that’s my income for those two years.

There’s that fear again.

“I don’t know how successful the next game will be,” he says.

But it might sell, like, not well at all.”

So for now, at least, it’s back to what he knows best.

“Make a thing, then sell the thing,” he laughs.

“That’s my plan.”

This feature originally appeared inEdge magazine.